Francis Field's History: 1792-1972

Posted, May 25, 2017

The West End and Square 13

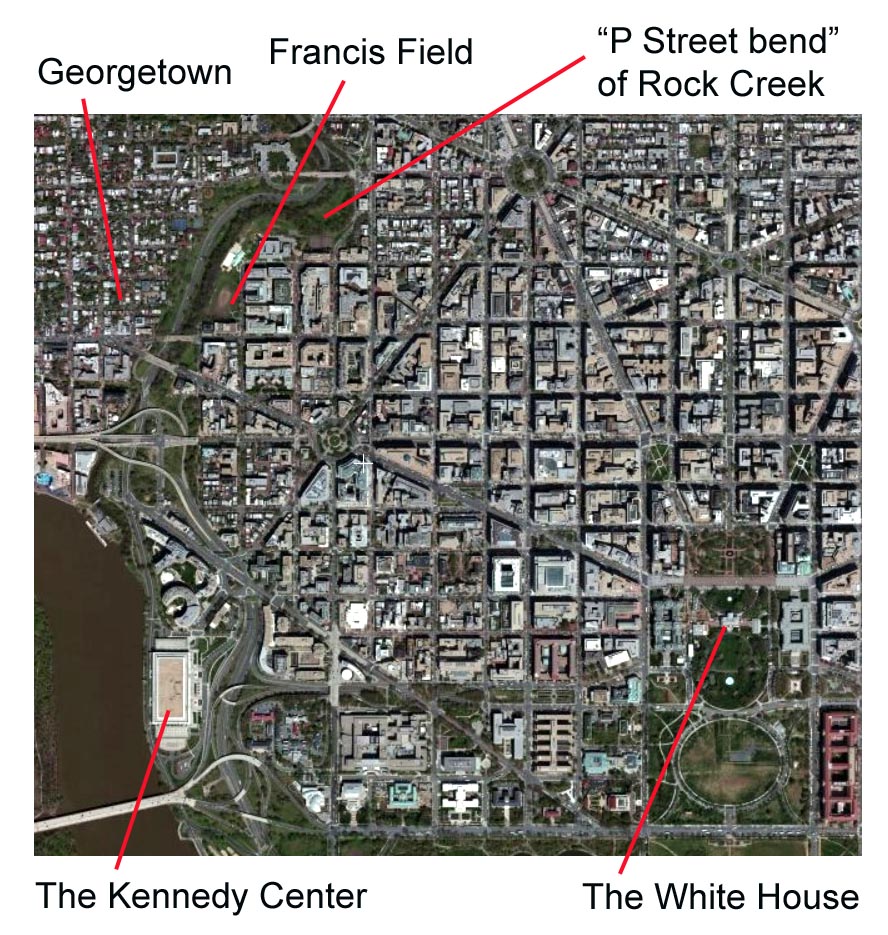

Francis Field can be easily located on most maps or satellite images of Washington, DC, because of its geographic location near what is known as the "P Street bend" of Rock Creek, a stream that flows south into the Potomac River.

On the west

side of Rock Creek is Georgetown, a historic district that was once a separate town.

On the west

side of Rock Creek is Georgetown, a historic district that was once a separate town.

The green areas on each side of Rock Creek are part of the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway, and make up the thin southern end of a much larger national park, appropriately called Rock Creek Park. It is one of the country's earliest national parks, having been established in 1890.1

A portion of Francis Field makes up part of that national park. The federal government started acquiring portions of the field in 1913 to provide a landscape buffer between the natural setting of the park and the urbanization of the capital city.

The location of the White House, at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, is shown at the bottom right of the image. Francis Field is about nine blocks west of the White House, and five blocks north.

Washington was a planned city, designed to be the seat of the federal government, and laid out by Pierre L'Enfant, a French-born artist who worked as a military engineer for George Washington's army during the American Revolution.

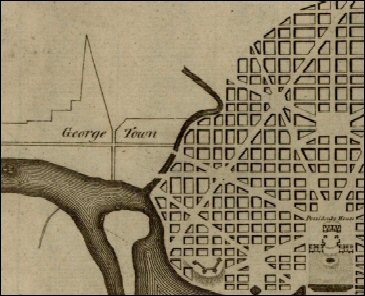

In March 1791, L'Enfant arrived in Georgetown, which was then in the state of Maryland. He stayed at an inn there, and every day crossed Rock Creek on the Bridge Street bridge (now the M Street bridge) to examine the location chosen for the new city and begin his famous plan. It was first published in March 1792. A portion of it is shown below.

On that

plan, "George Town," which is shown with only two main roads, actually had several streets at the time. Washington, DC—known then as the Federal City—was only lines on paper.

On that

plan, "George Town," which is shown with only two main roads, actually had several streets at the time. Washington, DC—known then as the Federal City—was only lines on paper.

A comparison of the satellite image above and the L'Enfant plan at left shows how closely his design of streets and open spaces was followed. However, L'Enfant intended for there to be only two bridges crossing Rock Creek: one at today's K Street in the south, and the other crossing at Pennsylvania Avenue in the north.

His plan also shows how he used Rock Creek and its "P Street bend" as a defining edge. The plan also demonstrates why the neighborhood where Francis Field is located today became known as the West End.

It was literally the western end of the Federal City and the District of Columbia. Georgetown remained a separate city until 1870 when its government was merged with Washington, DC.2

L'Enfant was fired before his plan was completed, and the drawing above—the first to be engraved and published—had been altered from L'Enfant's original by surveyor Andrew Ellicott.

Many critics believe, as one of them put it, that the surveyor "failed to understand precious nuances" of L'Enfant's artistic design.3

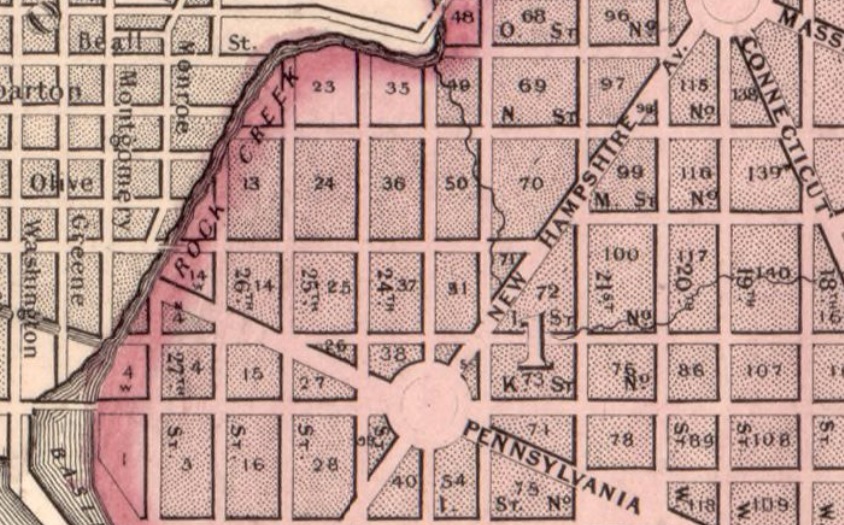

By the time Ellicott's next engraved map was published in July 1792, the Federal City had been named the City of Washington, and what we know now as the District had become the Territory of Columbia. The new map numbered the squares but did not show street names. These 1792 numbers remain in use for the most part today, defining the same blocks.

A map in Colton's Atlas, published in 1855, and shown below, uses those same designations for squares. Francis Field is located on Square 13, one of the squares below the P Street bend:

The Pennsylvania Avenue bridge had not been built when this map was published. It shows the existing bridges at M Street and K Street.

The Pennsylvania Avenue bridge had not been built when this map was published. It shows the existing bridges at M Street and K Street.

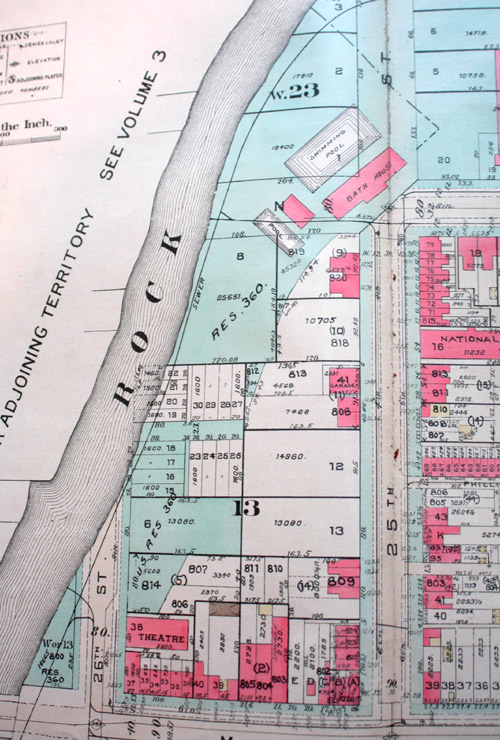

The streets are marked on this map, although not all are shown on this small detail. Then as now, Square 13 is bordered on the south by M Street, which was an extension of Bridge Street in Georgetown. Its eastern border is 25th Street. Rock Creek makes a small part of both its western and northern borders.

Thus, Square 13 is not a perfect rectangle. It became even more triangular in later years as the banks of Rock Creek changed.

The figure "1" in the center of this detail refers to the District's division into wards. At this time everything west of the White House was Ward 1. That part of Washington was known for many years as both the "West End" and the "Old First Ward."

The West End name stuck. Francis Field's location has always been in the West End, which has now become a desirable, up-scale neighborhood of Washington, DC; but it was not always so.

"Unsightly to the Verge of Ugliness"

In the early 1900s, the West End was one of the poorest areas of Washington. The wealthy built homes closer to the White House and the Capitol building. The northwest section of the West End became a largely African-American area, and what we know today as Francis Field was used by commercial enterprises serving that constituency.

Others exploited the vacant lots and open area in the center of the square for the dumping of ash and other debris. A good deal of it was thrown down the banks of Rock Creek, killing much of the vegetation that had existed.

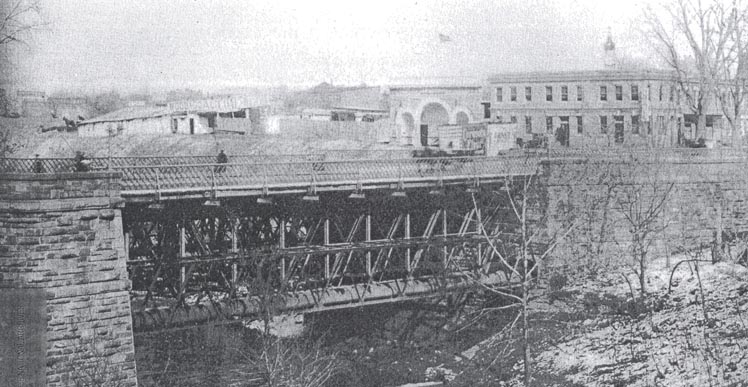

The best early photograph of Square 13 that we have found was taken from the Georgetown side of Rock Creek in 1911 and is shown below in large size. It was meant to depict the steel-truss M Street bridge, but it gives us a good view of the western edge of Square 13 at that time:

Although Georgetown had been annexed years earlier, this was hardly the concept that Pierre L'Enfant envisioned for the western entrance to his Federal City. It also shows the challenges that landscape architects and park planners faced in trying to build a scenic parkway along Rock Creek, which was already in discussion.

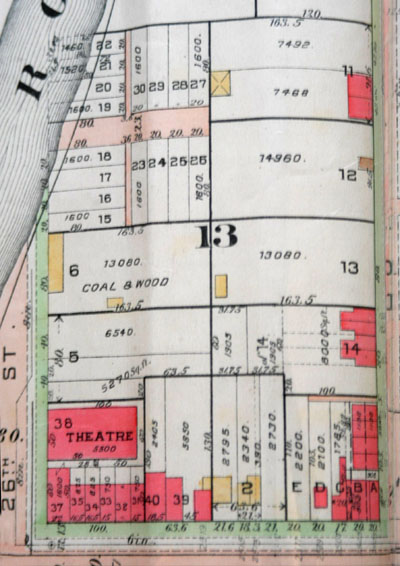

The detail of Square 13 from the Baist Real Estate Atlas of 1913 at left gives us some context for the photograph above. Wooden buildings are shown in yellow, brick buildings in pink.

The detail of Square 13 from the Baist Real Estate Atlas of 1913 at left gives us some context for the photograph above. Wooden buildings are shown in yellow, brick buildings in pink.

The substantial brick building on the far right of the photo, at the corner of 26th and M Street, was a bar and liquor store. That's an advertising sign of a giant bottle on its roof.

The building with the arches is the Blue Mouse Theater, which was where African-Americans in this part of the District went to see vaudeville, and soon, motion pictures. Theaters, like schools, restaurants, and churches, were mostly segregated at this period.

The wooden sheds in the photograph were no doubt those used by the coal and wood business shown on the real estate plat.

Square 13 did not become much more developed than this plat shows, and many of the lots were never built upon.

In 1901, a U.S. Senate committee called for an expert commission to improve the park system of the District. This resulted in the celebrated "McMillan Commission," named after its chairman, which recommended a unified system of parks and parkways, "commensurate with the dignity and resources of the American nation."4

Specifically mentioned for improvement was the Rock Creek valley between Pennsylvania Avenue and Q Street, which included Square 13 where Francis Field is located today. In its 1902 report, the McMillan Commission called that area "unsightly to the verge of ugliness."5

Landscape Architecture Problems, Solutions, and Aspirations

Among the solutions that were proposed and studied was one that involved filling in the Rock Creek valley between Georgetown and the West End, and running a road and the creek through a tunnel or conduit below.

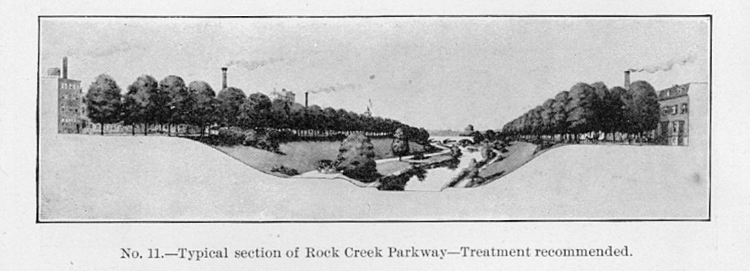

However, the Commission favored an "open valley" plan, with a scenic parkway that was isolated from the surrounding urbanization with a buffer area of trees and open space. It included the illustration below in its report:

With this treatment, visitors to the parkway would not look up and see smokestacks, telephone poles, outhouses, the backside of buildings, or unsightly industrial or commercial structures such as those on Square 13 at the time. The Commission stated both the problem and its solution:

The sights of the inland region between Pennsylvania Avenue and Q Street are for the most part shabby, sordid and disagreeable. It is therefore a very fortunate opportunity that permits the seclusion of the parkway in a valley, the immediate sides of which can be controlled and can be made to limit the view to a self-contained landscape, which may be beautiful, even though restricted.6

Advocates of the conduit plan, however— particularly those in Georgetown—continued to lobby for filling in Rock Creek Valley, which would create more property to develop.

In 1908, the engineer commissioner of the District, Major Jay J. Morrow, and his assistant, Captain E. M. Markham, conducted a detailed study of all plans, and published a report examining them.

In 1908, the engineer commissioner of the District, Major Jay J. Morrow, and his assistant, Captain E. M. Markham, conducted a detailed study of all plans, and published a report examining them.

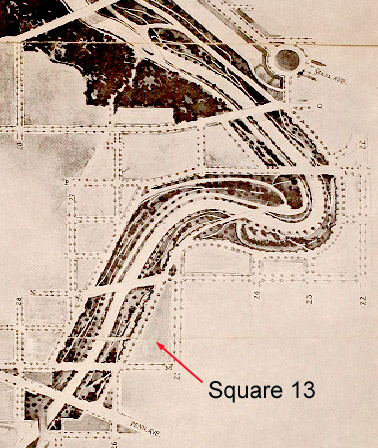

Building on the McMillan Commission's recommendation for an open but "self-contained landscape," they included a design for a large park extending over several squares around the P Street bend in Rock Creek, including Square 13. A portion is shown at left, with Square 13 indicated.

Morrow and Markham had high hopes for this extensive border park, and stated, with perhaps of bit of hyperbole, that this, particularly "the portion of the park between N and P streets, could be developed as the most beautiful urban park in the world."7

Between the parkway and the urban surroundings there would be "border streets" surrounded, in turn, by open, park-like squares that would encourage the building of attractive homes facing the parkway, and with scenic views across Rock Creek.

Morrow and Markham stressed that border streets should be laid out "so that the back of buildings could not be presented to view the park."8

Timothy Davis, an historian of Rock Creek Parkway, explains the architectural function of these "buffer zones" and border roads for the parkway's landscaping:

An important function of the border roads was to ensure that buildings faced toward the parkway, so that parkway users would see the handsome front facades, not the untidy backsides that might be exposed if adjacent buildings faced away from the parkway to surrounding streets. New buildings would only be allowed on the side of the street away from the park.9

Congress was eventually convinced that the "open valley" plan—and the designs of Morrow and Markham—made good sense. In 1910 it also established the Commission of Fine Arts, to advise on the government's buildings, monuments, and parks, with Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., as a member. Olmsted, a leading landscape architect, had also been a member of the McMillan Commission. He took a special interest in overseeing the plans for Rock Creek Parkway.

In 1913 Congress appropriated $1.3 million for the purchase of the private land necessary for the plan that Olmsted and others endorsed. No land was acquired at that time, however. In 1916, a House of Representatives commission reported on the private lots to be taken. The total cost for the lots on Square 13 was Of this total, $25,788 was estimated for lots on Square 13.10

In 1913 Congress appropriated $1.3 million for the purchase of the private land necessary for the plan that Olmsted and others endorsed. No land was acquired at that time, however. In 1916, a House of Representatives commission reported on the private lots to be taken. The total cost for the lots on Square 13 was Of this total, $25,788 was estimated for lots on Square 13.10

Lots 37 and 38, where the liquor store and the Blue Mouse theater were located, were the most highly valued, but the report suggested taking both lots in their entirety. The liquor store was described as a "two-story brick building" and Lot 38 was "covered by a motion-picture house."

The Blue Mouse, shown in the photo at left as it appeared in 1929, had only recently been constructed. Both lots had the same owner, Joseph I. Leary, and their estimated cost to acquire was $14,415—more than half of the cost for all of the lots on Square 13 that were recommended for acquisition. As it turned out, neither of those lots were purchased, and they remain today in private hands, currently occupied by the Embassy of the State of Qatar.

A School and a Pool

Economy measures resulted in other lots with existing buildings remaining in private hands, preventing the careful plans of Morrow and Markham, and those of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., from being fully implemented.

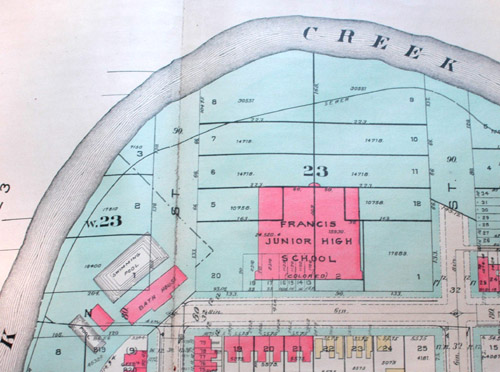

Construction did not begin on the parkway until 1929, by which time impediments to the architectural plan were erected on some of the border streets. In 1927 construction began on Square 23 for a junior high school for "colored" students. This was a large, modern building, but part of the District's racially segregated school system.

Construction did not begin on the parkway until 1929, by which time impediments to the architectural plan were erected on some of the border streets. In 1927 construction began on Square 23 for a junior high school for "colored" students. This was a large, modern building, but part of the District's racially segregated school system.

Contrary to Olmsted's plans, it was built with its back end facing the proposed parkway. Also constructed to the west of the school was a swimming pool—a part of the District's segregated recreation system.

Both are shown in a detail of the 1932 Baist Real Estate Atlas at left. The blue coloring represents government land. By this time, most but not all of the "buffer zone" for the parkway had been acquired.

The site of the swimming pool had been the favored site for the eastern end of a new bridge to replace the old M Street Bridge that was not in the L'Enfant plan. The newly created Commission of Fine Arts strongly opposed rebuilding the M Street Bridge, but lost the political battle to Georgetown business interests.

The placement of the swimming pool—with its bathhouse and wading pool—seemed to be an intentional measure to prevent the planned N Street Bridge from ever going foreward.11

According to the Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Francis Junior High School was dedicated on March 20, 1928, and the "New swimming pool for colored at 24th and N" was opened on July 14, 1928.12

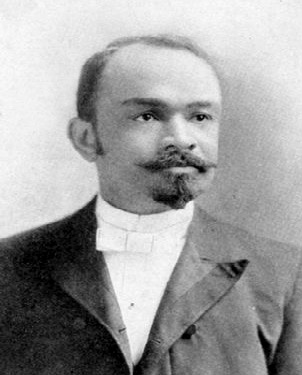

The school and the pool were named for Dr. John R. Francis (1856-1913), an African-American physician who was a former member of the District's Board of Education. He was a distinguished member of the Washington, DC, community, an associate of Booker T. Washington, and a pallbearer at the funeral of Frederick Douglass. An 1878 graduate of the University of Michigan, he served as obstetrician at Freedmen's Hospital in the District, and taught clinical obstetrics at Howard University.13

The school and the pool were named for Dr. John R. Francis (1856-1913), an African-American physician who was a former member of the District's Board of Education. He was a distinguished member of the Washington, DC, community, an associate of Booker T. Washington, and a pallbearer at the funeral of Frederick Douglass. An 1878 graduate of the University of Michigan, he served as obstetrician at Freedmen's Hospital in the District, and taught clinical obstetrics at Howard University.13

His portrait is shown at left. Francis Field is named for him today, although that name was not in common use until much later. Additional land on Square 13 was acquired by the federal government in the 1930s and became known as Francis Playground.

The new school and pool were well-built, modern facilities, and their location helped to improve the educational and recreational needs of the area. They also established the West End as a predominantly black neighborhood.

The movie theater was only one of the businesses on Square 13 that was known as an African American institution. Just around the corner on M Street was a poolroom, a barber shop, and a luncheonette. All of these remained while much of the rest of the Square was being acquired for the parkway's buffer.14

The siting of the pool and school, however, were not appreciated by the parkway's planners, who learned of the District

commissioners' plans about a year before construction began. Frederick Law Olmstead was not pleased, according to historian Davis:

The siting of the pool and school, however, were not appreciated by the parkway's planners, who learned of the District

commissioners' plans about a year before construction began. Frederick Law Olmstead was not pleased, according to historian Davis:

Upon learning in October 1926 that a swimming pool and bathhouse were being planned adjacent to the junior high school east of the parkway at N Street, Olmsted urged that plans for the parkway be finalized as soon as possible to ward against other such encroachments. The swimming pool and school building made it impossible to secure an adequate border road along the east side in this region without marring the view from the valley below.15

For his automotive parkway, Olmsted wanted to avoid the mistakes of railroads, who blighted their rights of way—and the enjoyment of passengers—by subjecting them to unattractive views of buildings' backsides. The new junior high school offered just such a view, as shown in the 1992 aerial view above. Residents of the buildings on the Georgetown side of the parkway got a view of the rear of a District school building—and its parking lot.

"Handsome Houses Facing the Parkway"

With America's entry into the First World War, Olmsted went to work for the U.S. Department of Labor, as a planner with the United States Housing Corporation, charged with building housing for munitions workers. He had served eight years on the Commission of Fine Arts, and declined to accept another four-year appointment. However, he volunteered to review landscape plans, and wrote several letters and memos regarding the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway during the early and mid-1920s.

In several of these, he commented on the "border roads" and suggested that "they enhanced adjacent property values" and that "handsome houses

facing the parkway" would serve several functions. They would provide "a more pleasant prospect for parkway users," and they would reduce "policing and maintenance problems" particularly the dumping of ash and refuse into Rock Creek, which had become a serious problem."16

In several of these, he commented on the "border roads" and suggested that "they enhanced adjacent property values" and that "handsome houses

facing the parkway" would serve several functions. They would provide "a more pleasant prospect for parkway users," and they would reduce "policing and maintenance problems" particularly the dumping of ash and refuse into Rock Creek, which had become a serious problem."16

While Congress had appropriated funds in 1913 to purchase the "buffer zone" properties, this was a slow process. As shown at left in the 1932 Baist Atlas plat of Square 13, several of the smaller lots adjacent to Rock Creek were still in private hands. In addition, several of the lots that had been purchased were in deplorable condition.

The 1932 plat also shows that the small houses on the east side of 25th Street had no clear view of the proposed "buffer zone" or parkway. The small lots shown half way between M and N Streets were in fact crowded "alley dwellings" in the slum known as Philips Alley, which was photographed in the muckraking 1909 book, Neglected Neighbors.17

Despite Olmsted's concepts, property values were not rising, and there was no incentive to build "handsome homes" facing the proposed parkway, which was still not completed.

In fact, just the opposite was true on Square 13. Much of it remained unpleasant, and parts were, quite literally, a junkyard.

According to Boyd's Directory of Washington and Georgetown, Lot 39, at 2519-2523 M Street was variously listed from 1909 to 1934 as the property of junk dealers Jacob and Myer Brenner. The Brenners seem to have entered the auto-wrecking business in the 1930s.

While their Lot 39 remained in private hands, the use of Square 13 as a dumping ground for scrap continued, even on the lots the government acquired for the buffer zone. Davis describes the difficulty in clearing these government-owned lots and the Rock Creek banks for construction of the parkway:

One of the most troublesome spots was a junkyard that had grown up behind the old Blue Mouse Theater at the corner of 26th and M streets. This unsightly accumulation of autobodies and assorted scrap metal was finally removed by an unemployment-relief crew in February 1933.18

Another Depression-era measure that affected Square 13 and the future of Francis Field was the "Capper-Crampton Act" of 1930, one provision of which provided for the purchase of park and playground areas in Washington, DC.19

This resulted in the acquisition, over the next ten years, of most of the rest of the lots on Square 13 by the government. At this point, Washington, DC, was administered by congressionally appointed commissioners. In 1972, however, when the District was granted "home rule" government, the "Capper-Crampton" recreational facilities and playgrounds were transferred to District management, resulting, in the divided management of today's Francis Field.

This resulted in the acquisition, over the next ten years, of most of the rest of the lots on Square 13 by the government. At this point, Washington, DC, was administered by congressionally appointed commissioners. In 1972, however, when the District was granted "home rule" government, the "Capper-Crampton" recreational facilities and playgrounds were transferred to District management, resulting, in the divided management of today's Francis Field.

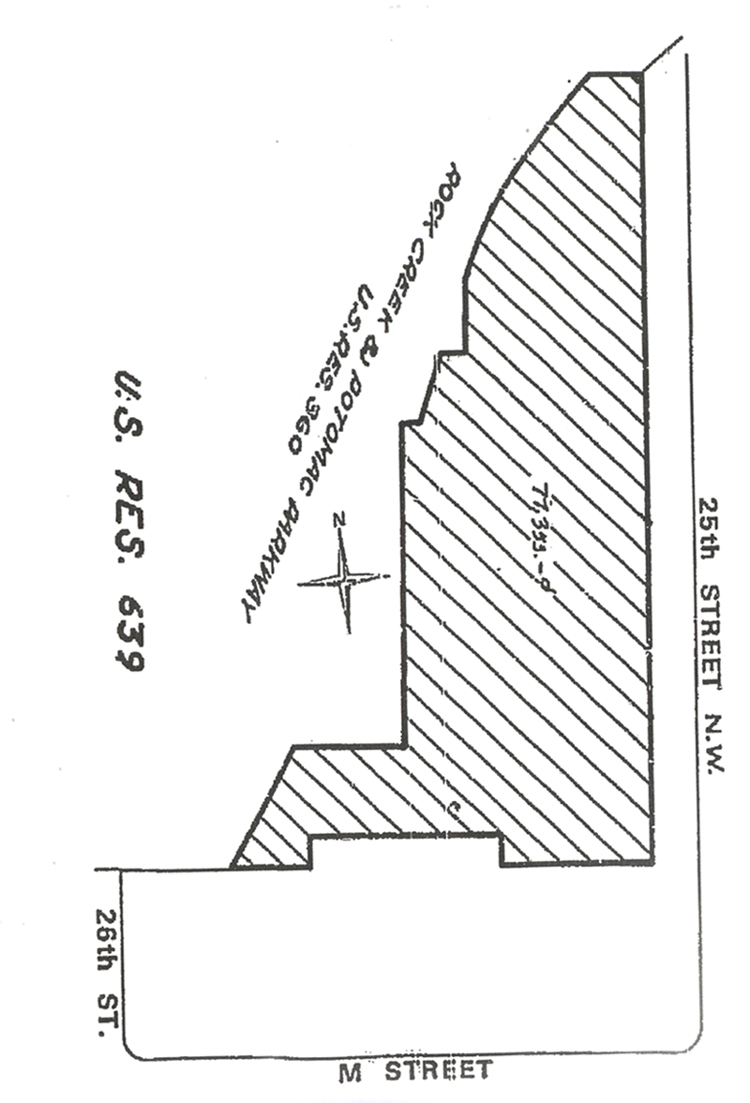

While the "buffer zone" for the parkway became U.S. Reservation 360 (shown in blue on the plat above), the Capper-Crampton properties, acquired between 1931 and 1941, became U.S. Reservation 639. A plat is shown at left.

L'Enfant's plan, modified by Ellicott in 1792, had only 17 "reservations," mostly large areas for public grounds. As the streets and roads became defined, many small triangles and squares became added and numbered. (Reservation 1 is the White House Grounds and Ellipse.) In 1893, there were 246 numbered reservations. By 1894, there were 301, and these became the "official basis for the park system in Washington.20

The new Reservation 360 for Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway was acquired under a 1913 law to serve a purpose primarily related to landscape architecture. Reservation 639 was acquired under a 1930 law to provide economic stimulus and playground space. The occupied lots along M Street, at the south of the square, were too costly to acquire for either purpose. They still remain in private ownership .

The section of the parkway between K and P Streets was the last to be completed. It was opened in October 1936, although there was still much work to be done along the eastern bank.

The section of the parkway between K and P Streets was the last to be completed. It was opened in October 1936, although there was still much work to be done along the eastern bank.

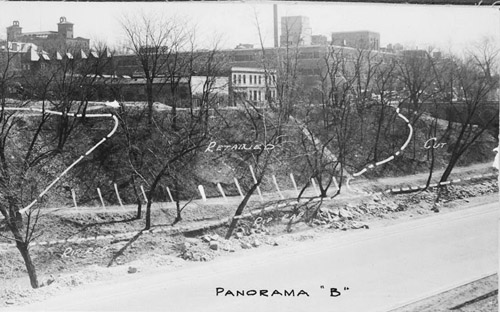

In the spring and summer of 1940, Rock Creek was "rechanneled" south of P Street, which altered both the stream bed and the banks adjacent to today's Francis Field. A construction photograph at left, part of a panoramic series, shows the view looking east.

This shows in the center the buildings at the corner of 26th Street and M, which are the former Blue Mouse theater (which had become the Mott by this time) and the former Leary liquor store.

The large building behind them is the former Chestnut Hill Farms dairy plant. At the far left is the former Columbia Hospital. Abutting the south end of the field and playground were the back ends of the one- and two-story buildings on M Street.

If we arrange the photo above with three others, we can recreate the panorama of Francis Field, shown below. It gives us a view, left to right, of the parkway at the P Street bend, with Francis Junior High School (at the juncture of the first and second photograph), the buildings on the east side of 25th Street, and those on the south side of M Street between 25th and 26th:

A larger size view of this panorama is on this website. It shows that Francis Field was being used as a staging area for the construction, and that a temporary road was constructed, on which trucks can be seen in the third photograph from left.

In the second photograph from left, the only substantial building with an attractive facade is the National Lithography printing plant. The panorama shows the potential of 25th Street as the type of border road that Olmsted envisioned, with handsome buildings facing the park and parkway.

But this use of this site remained unappreciated and underutilized during most of the 20th century.

But this use of this site remained unappreciated and underutilized during most of the 20th century.

At left is a 1963 photograph showing the architectural fabric of the corner of 25th and M Streets. Behind the red brick apartment building is a baseball backstop, and the bathhouse of the Francis Swimming Pool can be seen at the extreme left of the photo. A larger version is on this website.

At the extreme left of the photo is a portion of a remaining junkyard, this one used for scrap metal from the Gichner Iron Works, which was located on 24th Street, where the Fairmont Hotel is today. Gichner made iron grates for windows, and also had fabricated the White House gates.

At this period, the northern part of the West End was still light industrial, with auto garages, printing plants, and a dairy plant. A companion photograph shown below, taken the same day as the one above, shows the buildings on M Street west of this corner lot. The same white automobile is seen in both. It shows the nature of the retail businesses on the south end of Square 13, which were largely automotive. The Gichner scrap yard is at left.

Until 1954, both the schools and playgrounds of the District were segregated, and the integration of facilities did not draw whites to the formerly black facilities. Given this junkyard architectural fabric on the south side of Square 13, and what was no doubt a poorly maintained baseball field dominating the rest, it is perhaps not surprising that the existence of the adjacent parkway did not attract builders of handsome houses to the border road of 25th Street.

Fifty years after the government began purchasing lots on Square 13 to try to ameliorate the "ugly" and "disagreeable" nature of the area along Rock Creed between L and P Streets, not a single handsome front facade faced the parkway from this area.

The West End Defined: 1972

Washington, DC, and the District of Columbia went through several forms of government in the 19th century, as Congress attempted to govern the nation's capital. In 1874, Congress abolished the District's territorial government, and gave the President of the United States authority to appoint three commissioners, approved by the Senate to govern the District.

That form of government remained in effect until 1967, when President Lyndon Johnson convinced Congress to adopt a single, presidentially appointed commissioner, and a nine-member council.

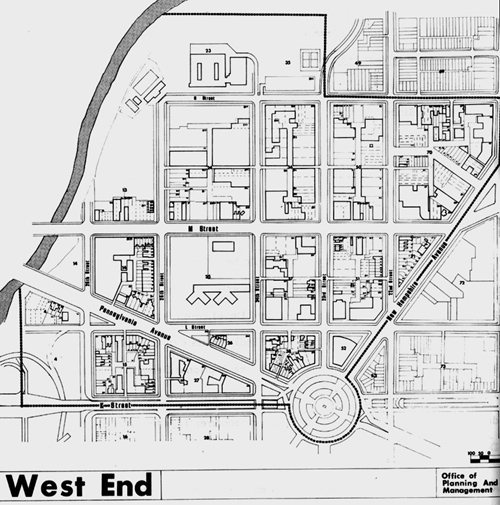

The single commissioner was quickly termed the mayor-commissioner, and this form of government was in place in April 1972, when the District's Office of Planning and

Management sent Mayor-Commissioner Walter Washington a 31-page proposal for an urban renewal program to redevelop the West End into a "new residential community."21

The single commissioner was quickly termed the mayor-commissioner, and this form of government was in place in April 1972, when the District's Office of Planning and

Management sent Mayor-Commissioner Walter Washington a 31-page proposal for an urban renewal program to redevelop the West End into a "new residential community."21

As shown on the map at left, the West End was quite specifically defined by K Street on the southwest, Rock Creek on the west, and New Hampshire Avenue on the east. On the north, in included Francis Junior High School, the swimming pool, and the two tennis courts that were then part of the Francis Recreation Center. A larger version of the map is on this website.

The District government and its agencies were still under federal control. The report was funded mostly by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. It remains the single best document that defines the borders and boundaries of the West End neighborhood of today.

The report focused on the potential of the West End at that time, but was brutally descriptive of the existing conditions. It was called "an underutilized area of dreariness and decay." The report noted that "only a few private structures have been erected in the past ten years." It found that "over 58% of the West End is vacant, unimproved (parking) or non-taxable." It was "unsafe at night and an eyesore by day." Finally, the report stated that ""the West End is underused an a detriment to the District rather than an asset."22

As far as remedies, the New Town in the West End report recommended rezoning sections of the West End from light industrial to high-density residential. It said in addition, "what the area needs in not more office buildings, but more people continuously in the area to give it a human quality after business hours."23 These recommendations were followed, but it took more than 30 years to transform the West End into the desirable neighborhood that is today: what the report envisioned as "one of the most desirable residential neighborhoods in the city."24

During that 30-year period, while the West End was transformed by farsighted planners and developers, Francis Field remained stuck in time, a neglected dirt field and an eyesore—more of a detriment than an asset to the city and its surrounding neighborhood.

See the next section, "Francis Field: A Study in Neglect."

Notes

01. This is year in which the legislation was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison. See Barry Mackintosh, Rock Creek Park: An Administrative History (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1985), p. 13. [ Internet Archive ]

02. Congress repealed the charter of Georgetown, but kept its name as city in passing "An Act to provide a government for the District of Columbia" on February 1, 1871 (16 Stat §40, 428).

03. Iris Miller, Washington in Maps: 1606-2000 (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2002), p. 44.

04. Charles Moore, ed., The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia (Washington, DC: U.S. Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, 1902), p. 8. Hereafter referred to as McMillan Commission Report. [ Internet Archive ]

05. McMillan Commission Report, p. 11.

06. McMillan Commission Report, p. 86.

07. District of Columbia, Board of Commissioners, Report Upon Improvement of Valley of Rock Creek (Washington, DC: United States Senate, 1908), p.27. Hereafter referred to as Morrow and Markham. [ Internet Archive ]

08. Morrow and Markham, p. 3.

09. Timothy Davis, Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway: History and Description (Washington, DC: National Park Service, Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS No. DC-697, 1992), p. 62. [ Library of Congress link ]

10. Report of the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway Commission: 1916, (Washington, DC: House of Representatives, 1916), p. 42.

11. See Timothy Davis, pp. 88-91.

12. "Chronicler's Report for 1928," Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Vol. 31/32 (1930), p.372.

13. Francis's biographical information is taken from the listing, "Francis, John R.," Notable American Black Men,, Second Edition (Farmington Hills, MI: Thompson Gale, 2006), n.p.

14. LaBarbara Bowman, "Building Boom Hits West End with a Sour Note," Washington Post, March 27, 1977. [ web link ]

15. Timothy Davis, p. 93.

16. Quoted in Timothy Davis, p. 83.

17. Charles Frederick Weller, Neglected Neighbors (Philadelphia: John C. Winston Company, 1909), p. 26.

18. Timothy Davis, p. 95.

19. This act, which had a lengthy title, was passed on May 29, 1930, and signed by President Herbert Hoover. It also included the purchase of land in Virginia and Maryland for the George Washington Memorial Parkway along the Potomac River. It took its popular name from its two sponsors, Senator Arthur Capper of Kansas,, the chair of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, and Rep. Louis Crampton of Michigan, chair of the House Committee on the District of Columbia. The citation for the statute is 46 Stat. 482.

20. Elizabeth Barthold and Sara Amy Leach, L'Enfant-McMillan Plan of Washington, D.C.,(Washington, DC: National Park Service, Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS No. DC-688, 1993) p. 33. [Internet Archive]

21. District of Columbia Office of Planning and Management, New Town for the West End, (1972), p. 1.

22. New Town for the West End, pp. 2, 9, 11, 13.

23. New Town for the West End, p. 15.

24. New Town for the West End, p. 20.